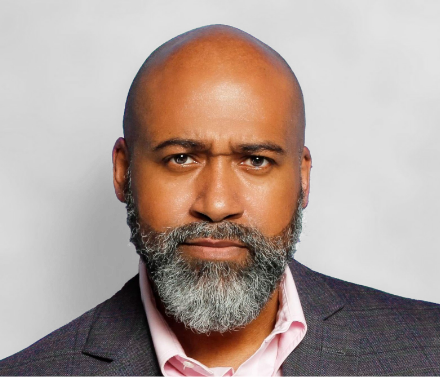

I USED TO WORK in software engineering at Khan Academy. Khan Academy has this big mission of a free world class education for anyone, anywhere. It does that through an asynchronous format of videos and exercises at your own pace. We had always wondered whether we could provide that same free, high-quality, world-class education through a live synchronous format, something even higher touch; humans interacting with each other, such as mentoring and/or tutoring. We know tutoring is highly effective, but it’s often very costly and hard to scale.

A lot of people hear ‘personalized learning,’ and they think of learning in front of a computer with no humans there, but personalized done right should be personal.”

It wasn’t until a month or so into the pandemic that the need for this really became clear. Unfortunately, students were already grade levels behind pre-pandemic, but the pandemic put them even further behind because of all the lost learning. The pandemic really exposed the issues of the education system. It’s kind of like a tide went out and left all the issues that had previously been there on the shore.

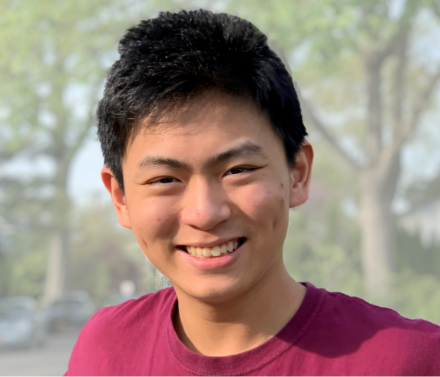

But there was also this norm change in how students thought about things. Five years ago, it would’ve been weird for a group of high schoolers from around the world to get onto a Skype call and learn from one another. The pandemic changed that. Now we have people getting on Zoom calls together, learning from one another. So, we saw the potential for a free, peer-to-peer tutoring platform that could connect people from around the world.